Since 2008, I have been working with a team of dedicated and resourceful people on the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain’s online forum and its associated social media, including its YouTube channel that has over 2.2 million views, and its Twitter accountthat currently has over 13 thousand followers. In September of last year, a handful of friends and I co-founded the organization Ex-Muslims of North America, or EXMNA. We have set up local meetup groups in 11 cities in just over a year, and the organization continues to grow. In just a few years, I’ve seen the idea of apostasy from Islam grow exponentially, and today there are a number of open, public Ex-Muslim freethinkerswho are writing, blogging, podcasting, doing interviews, speaking on panels at conferences, and generally putting their names, faces, and voices out there.

This is not to say we are all alike. In fact, this is important: I can’t say that any one of us speaks for all people who have left Islam; each of us really only speaks to our own experiences, although there definitely are commonalities. Still, the fact that there are so many diverse Ex-Muslim voices out there now – and the number keeps growing – is something I cherish very much, because I clearly remember the time before all this.

I was born and raised in Pakistan, lived in the US for many years, before settling in Canada. I had questions about Islam from a young age: aspects like the second class status of women in its scriptures and laws, the absolutely insane concept of hell and eternal torture, and general questions about things like, if god made everything, who made god, etc. etc. After trying to silence those questions in myself, I finally realized around age 19 that I was just not cut out for this religion thing.

Back in the late 1990s when the Internet was just learning to crawl, dial-up was the norm, and Google was yet to be born, I thought I was the only person in the entire world to have realized I couldn’t believe in Islam anymore. That I was not Muslim anymore. Islam is taught to most of us from Muslim backgrounds in such a way that it becomes woven into the very basic fabric of our identity. This is why one of the most common statements every Ex-Muslim makes at some point or another is: “I thought I was the only one!” Over the last 6 years that I’ve been involved in this movement, I have personally gotten to know a few thousand Ex-Muslims online and offline, and that is the most common line that almost all of them say at some point.

In the next few minutes, I will suggest some ideas about why I think this is so.

Probably more than any other religion practiced today, Islam permeates every aspect of life, from spiritual concerns to daily habits like what to eat, what to wear, who to associate with, and even how to go to the bathroom. When every aspect of your being is ruled by an ideology, that ideology comes to define your being: in this way, Islam defines for many Muslims the very act of being human. And of course, the flipside of “Muslim = human” is “non-Muslim = non-human”.

If you study anthropology, you see that every human civilization or social group has its own set of in-group and out-group parameters. All humans have a tendency towards tribalism, towards ‘us vs. them’ thinking, to various degrees. (Including some atheists!) For Islamists, the matter is taken to an extreme, and given divine sanction. Islam defines all outsiders as “Kafir”: a concept whose implications are deeply misunderstood by those who are outside. For both the violent type of Islamists, like Daesh, a.k.a. the “Islamic State”, and for the supposedly non-violent Islamists who go around trying to institute shariah law and promote dawah or Islamic evangelism while holding social views that belong in the 7th century, the ‘Kafir’ is a kind of sub-human category.

The Quran uses the term ‘Kafir’ 482 times in various derivations to describe non-Muslims, particularly pagan non-Muslims (it makes special dispensations for Christians and Jews, though nowadays, they tend to get lumped in with the poor pagans too). The word ‘Kafir’ technically means someone who denies or “covers” up the truth – the ‘truth’ of course presumed to be Islam. So Islamic belief entails that Islam is the only truth.

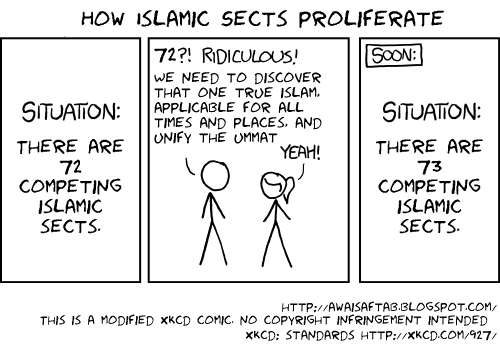

The problem is that violent sectarianism – as we’ve been hearing about by Pervez Hoodbhoy and so many other speakers – is so deeply enmeshed in Islam and its history, that while claiming that the “Muslim Ummah” is made up of a billion or more people and constitutes the “fastest growing religion” (a dubious claim), most Muslim sects actually don’t recognize large sections of that Ummah as Muslim in the first place! Besides the big Shia-Sunni split, there are multiple splits within those 2 groups, then there are the Ahmadis, and the Sufis, and sub-sects within those as well. And members of most of these groups will be quick to tell you that all those other groups don’t follow the “Real Islam™”.

(image source: A Myth in Creation – blog by Awais Aftab)

(image source: A Myth in Creation – blog by Awais Aftab)

For most Muslims, being labeled a ‘kafir’ by another Muslim feels like one has committed a kind of treason to one’s family and community. Daesh and other Islamist terrorist groups rely on the doctrine of Takfir (calling somebody else a Kafir) as their ideological basis. This is how they justify – to themselves and to their new recruits – massacring not just non-Muslims, but also thousands of people who identify as “Muslim”, whether they are Sunni, Shia, Ahmadi, Kurd, or anyone else. Each group’s ever narrowing definition of “Muslim” (which is to say, ever narrowing definition of “human”) marks everyone else in the world as Kafir: a sub-human who doesn’t deserve the same rights. It is a terrible derogatory term, on par with any horrible racial slur used to dehumanize an entire group.

This is the paradox at the heart of religious identity politics and its liberal apologism. Do people have the right to self-identification? (Yes!) Do we accept that anyone who claims to be Muslim is, in fact, Muslim? (Err. Yes?) Anthropologist Talal Asad, from the City University of New York, writes in his essay Anthropology of Islam, “A Muslim’s beliefs about the beliefs and practices of others are his own beliefs.” This issue is part of most Muslims’ belief system: who is and isn’t a Muslim? What is a “real Muslim”? What is the “Real Islam™”?

So, we are left with the dilemma faced by so many well-meaning liberals: that awkward situation of having to accommodate beliefs that are themselves unaccommodating, in the name of accommodating all beliefs.

As those who chose to leave Islam, Ex-Muslims are often seen as having devolved, having debased themselves to become a ‘kafir’: in other words, having betrayed their very humanity. This choice is naturally, and for a good reason, seen as a threat to the supremacist thinking promoted by Islamism that Islam is not only the best religion, but is the natural state of humanity, which is why some Muslims use the word ‘revert’ when referring to converts to Islam.

So it’s no wonder that people who leave Islam, whether they call themselves Ex-Muslim, apostate, or anything else, tend to face social ostracism, sometimes to the extreme. They tend to face isolation from family members, emotional blackmail, including alienation from younger siblings and their own children if they have them, and financial abuse. What kind of twisted, evil person voluntarily gives up his or her humanity?

Every Ex-Muslim has thought after they left Islam that they were the only one. With the Internet now, it is becoming much easier to find other like minded people, but the sense of isolation in new apostates is still strong, especially in their immediate surroundings, among their families, their neighborhoods, and their friends. Just yesterday, I met two siblings who had lived for years in the same household as closeted atheists, both thinking they were alone in their apostasy. And this situation is far from unique.

Every once in a while, we hear of an honour killing or a suicide. But death is only the extreme scenario. More often, many Ex-Muslims live with a steady barrage of microaggressions – everyday pressures to conform, to hide their lack of belief, to go through the motions , to wear a hijab, to marry a Muslim, and much more. I’ve known Ex-Muslims who have to pretend to fast, or actually remain hungry and thirsty for days against their will, because they live under the watchful eyes of religious family members. Many of the younger apostates are unable to be ‘out’ about their beliefs because they rely on their families for financial support, not to mention the emotional dependence ingrained into all of us as part of Muslim family structures.

The more Ex-Muslims speak up and reclaim the terms ‘Kafir’, ‘Murtad’, and with them, their right to be heard, their rights as humans to follow their own conscience without having to pretend, the more Islamists lose that ideological power that comes from what they see as their “divinely ordained” right to define who is and isn’t human.

One of the best and most efficient ways to stave off Islamism is to give platforms to diverse Ex-Muslim voices. Diluting the identity politics that is the lifeblood of Islamism is possible. Moderate Muslims often avoid supporting Ex-Muslims, perhaps out of fear of being called Kafir themselves. But more and more are realizing that we are not anti-Muslim. We may criticize Islam, like we do all religions, but we stand in solidarity with anyone, including Muslims, when they are being targeted out of hatred and xenophobia. Allowing the space for apostasy can give breathing room for variations and reformations within Islam as well. Islamists want us to believe that by leaving Islam, we lose our place as humans, and we lose our identities. But we don’t. What we actually lose is their hold on our definitions for ourselves. For us, Islamists no longer get to define what is and isn’t human. We think for ourselves. And that is what really, really scares them about us.

We Ex-Muslims tend to use LGBTQ lingo, because there are actually striking similarities among the lived experiences of both types of people, particularly the dehumanization and isolation they face within their own families and communities. Yesterday was “Coming Out Day”. I see this conference as a celebration for many Ex-Muslims who have come out to each other and to themselves. And those who will find inspiration in the days and conversations to come.